This morning, after the people-tunnel dissolved, I tried to squeeze myself onto the train. Aaaand, I failed, surprised by the doors that literally snapped closed in my face. Excellent. At least they didn’t hit my boobs, I thought to myself, still curious as to the strength of my implants. (On my first day back to work after my second surgery, I had an unfortunate incident with the small sliding doors at the T ticket entrance. It hurt, and it taught me to always put my arm up to lead the way through the jumpy sliders.)

When I realized that I had failed to board, I looked around and laughed. Of the over 100 or so people who had tried to board that subway train, I was the only one who hadn’t successfully pushed my way on. Part of me was mad, another part embarrassed, and another part, totally amused.

Not more than a second later, a friend of mine that I haven't seen in far too long walked over to me. I’ll call this friend “Angela.” Angela had just gotten off the train on the other side of the tracks. We hugged, and we laughed about the fact that I was the only one left on the platform as the train pulled away.

Angela is a breast cancer survivor, seven years out. Angela and I got to talking, actually, about “Betsy” whom we both know. The sick feeling returned and even though I admitted that feeling to Angela, it didn't go away. Then Angela told me this story.

Recently, Angela had gone to her doctor for her annual mammogram. She was telling the rad tech about Betsy and about how hard it has been for her to see Betsy battle her breast cancer recurrence. The rad tech replied, “Well, you know that you’re never really cured. It’s just in remission.” My bowl of Cheerios almost came up as fast as it had gone down.

Recently, Angela had gone to her doctor for her annual mammogram. She was telling the rad tech about Betsy and about how hard it has been for her to see Betsy battle her breast cancer recurrence. The rad tech replied, “Well, you know that you’re never really cured. It’s just in remission.” My bowl of Cheerios almost came up as fast as it had gone down.

In the end, it was wonderful to see Angela today. But I'm sure we both left each other in a similar state -- grateful for how lucky we've been and for the people that have helped us through it; fearful that that stupid mammogram lady could be right.

Now let me be clear, there are unbelievable nurses, doctors, PAs, and rad techs out there and I have written about several of them. But this particular post is not about these great people. This post is about the toxic ones; the ones like that awful rad tech.

Now let me be clear, there are unbelievable nurses, doctors, PAs, and rad techs out there and I have written about several of them. But this particular post is not about these great people. This post is about the toxic ones; the ones like that awful rad tech.

When I arrived at my office this morning, I wanted to break down in tears at the thought that I may be fooled by the thought of a cure. I was even willing to break my rule about not crying in front of people at work (alone in the bathroom is fine).

In the end, I didn't cry in front of anyone or even in the bathroom alone, not because I was strong, but because I had work that I needed to do. After promising myself that I could break down after my work was done, I sat down at my desk and did my job. Now I realize that this morning, that job rescued me.

A fellow blogger recently wrote a post about his experience with a toxic nurse. I loved this post. I'm sure that every person who has spent a lot of time getting medical treatment could share a similar story about a crappy clinician. I'm sure that each story would break my heart, too, because many patients (like me) are incredibly vulnerable. And to vulnerable people, any medical person as thoughtless as these ones are absolutely poisonous.

Now that I sit in the comfort of my own healing chair and type out these thoughts, I feel differently than I felt this morning. Tonight I don't feel sick at all. Instead, I just feel mad.

I wish I could meet that rad tech. I wish I could tell her what her fly comment meant to Angela and to me. I wish I could explain to her how crushing it feels for cancer patients to hear anything but that everything is going to be OK.

Then I wish I could tell her that she’s absolutely freaking wrong. Because she is. I’ve seen it with my own eyes and heard it with my own ears. The piece of paper that the chemo nurse uses to check my name, my birthday, and my infusion dosages -- it says “curative intent,” and I know that thousands of other patients' papers say that, too.

I wish I could meet that rad tech. I wish I could tell her what her fly comment meant to Angela and to me. I wish I could explain to her how crushing it feels for cancer patients to hear anything but that everything is going to be OK.

Then I wish I could tell her that she’s absolutely freaking wrong. Because she is. I’ve seen it with my own eyes and heard it with my own ears. The piece of paper that the chemo nurse uses to check my name, my birthday, and my infusion dosages -- it says “curative intent,” and I know that thousands of other patients' papers say that, too.

I'd also tell that woman what Dr. Bunnell says at the end of every appointment -- I think you're going to be fine, he tells me (OK, I have to ask him to say it, but still, he does). I'd tell her what I know about cures -- what Dr. Bunnell told me the night back in August when he told me that my cancer was HER2+: HER2+ cancer may be the first type of cancer that we cure. C-U-R-E. Cure. I want to repeat that word over and over and tell her what Dr. Bunnell has said many times (unsolicited, in fact) -- "We're going for the cure."

Of course, I am fully aware that one’s intent does not always indicate the outcome. No cancer patient needs to be reminded of what that word could mean. But shame on that lady for questioning the possibility of a cure. Shame on her for taking someone’s hope and dashing it; taking a woman's future and doubting it.

Of course, I am fully aware that one’s intent does not always indicate the outcome. No cancer patient needs to be reminded of what that word could mean. But shame on that lady for questioning the possibility of a cure. Shame on her for taking someone’s hope and dashing it; taking a woman's future and doubting it.

I admit, in most ways, it's not my natural instinct to push onto a train or to fight against a comment that feels so devastating to me. I'm certain that today wasn't the last time that I'll be left alone on the Orange Line platform or hear an opinion about cancer and want to bawl my eyes out. But I also know that like all patients with serious illnesses, I need to focus on the positive; surround myself with people and messages that give me hope and strength. Like my Dad told me early on, I need to get mad, and fight. Because there is a cure and I join thousands of women who are going for it. Oh, and to that rad tech out there, I want you to know that even if there weren't a cure, or even if my cancer (Heaven forbid) does come back, I'd still try to tell myself every morning -- I'm going for it. No matter what you say.

* * *

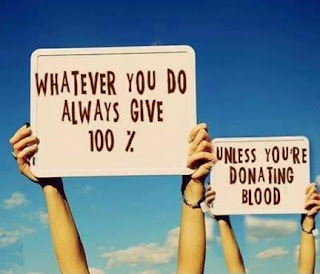

P.S. A wonderful woman from Canton shared this image with me and I had to pass it along. Thanks Susan!

No comments:

Post a Comment